A coalition of NGOs raises concerns over the current state of the draft National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) within the European Union as the European Commission is due to present the “State of the Energy Union”. In a scathing assessment, the NGOs have highlighted several significant shortcomings, including a lack of alignment with the EU’s own energy and climate ambitions.

While in some areas the energy and climate transition seems to be moving in the right direction, there is still much to be done for EU countries to align these efforts with the Paris Agreement’s goal.

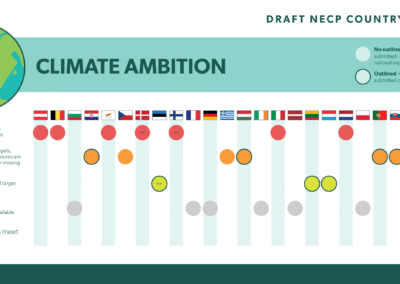

One of the most worrying aspects highlighted in the assessment is that several countries are not even meeting the minimum EU climate and energy requirements for 2030. Notably, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Italy, and the Netherlands are failing to meet set EU targets and their national share in cutting emissions to reach an EU-wide target of net 55% emissions reduction by 2030.

This is without mentioning that the EU´s overall climate ambition remains alarmingly off-track with the necessity of keeping citizens safe from dangerous climate impacts. A true commitment to its fair contribution to limiting global warming to 1.5°C should entail significant short-term emission reductions and achieving at least a 65% reduction in gross (or 76% in net) emissions by 2030.

Overall Assessment – Main findings and recommendations

The draft NECP updates could be the opportunity for Member States not only to meet and contribute to the new 2030 EU climate and energy targets – which they must do – but also to ensure that national climate and energy targets, policies and measures go beyond those targets and bring the EU’s emission reductions closer to a 1.5°C compatible trajectory. Both objectives are severely threatened by the fact that 12 out of 27 Member States (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Malta, Romania, Poland) have not submitted their draft NECP updates as of 30 September 2023. This late submission is not only in breach of EU legislation (Art. 14. Of the Governance Regulation), but implies that Member States lack a comprehensive plan to accelerate decarbonisation across all sectors in the next six years.

The draft NECP updates that have been submitted, on the other hand, still have large room for improvement, notably on the ambition levels and planning details. Luckily, Member States still have the opportunity to make them better until the final NECP submission deadline in June 2024, an opportunity which they must take. The European Commission must hold them accountable for the quality of the plans, and make recommendations that will ensure that the EU gears towards higher climate ambition.

Based on the assessment of the available plans, we have developed a set of recommendations to ensure that the NECP updates are fit for purpose:

- Increase the level of climate ambition

- Increase the ambition on energy savings

- Increase the ambition on renewables

- Develop more robust policies and measures

- Phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible

- Stay away from false solutions

- Plan to phase out fossil fuels subsidies

- Significantly improve public participation

These recommendations are further detailed below. The assessment criteria are based,among others, on the set of criteria CAN Europe and WWF developed earlier for strong NECPs.

Increase the level of climate ambition

In their plans, Member States are required to include national 2030 climate targets for both the non-ETS (altogether the buildings, road transport, agriculture, waste and small industry) and the LULUCF (land use, land use change and forestry) sectors. In this overview, we notably look into the Member State’s level of climate ambition for non-ETS sectors. We have also assessed whether projections with existing measures (WEM scenarios) and additional measures (WAM scenarios), as well as the policies and measures (PAMs) in the plans, are in line with the 2030 non-ETS targets. Details on the methodology are provided in Annex I of this report.

The minimum EU requirements for 2030 in non-ETS sectors are set in the Effort-Sharing Regulation (ESR). The ESR mandates each Member State to meet a specific level of emission reductions in non-ETS sectors, with the aim of achieving an overall EU target of -40% emission reduction in those sectors by 2030 (compared to 2005 levels). The current ESR target is however still unambitious and insufficient: to be in line with the Paris Agreement goal, at least 50% reductions would be needed in the ESR sectors.

Several of the countries that have submitted their draft NECP updates do not show the necessary level of climate action that would be required not only to align with a 1.5°C compatible trajectory, but also to meet the minimum EU requirements for 2030.

In fact, some of the countries that submitted their draft NECP update explicitly mention that the planned levels of action are not even in line with the respective binding ESR obligations (Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands). This is not to say that the remaining countries have done their minimum job. On paper, Estonia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden would all meet the ESR requirements. However, for some of them (Portugal, Slovakia, Sweden) projections with existing and additional policies and measures (WEM and WAM scenarios) are either missing or not credible in the current political context. Croatia and Lithuania also meet their minimum targets. However, it is worth flagging that a significant discrepancy exists between data used in the plans and European Environment Agency (EEA) data on historical emissions, to the point that both countries would fail to meet their respective targets if EEA data were used for the 2005 baseline (instead of data provided by the national governments in their draft NECP updates that refers to a higher baseline). This should be scrutinised by the Commission.

In most cases, PAMs are inadequate to meet the set targets. In some cases, countries have simply laid out existing measures (Denmark, Finland, Sweden), which are either not aligned with additional policies (WAM) scenarios, or reflect frozen policy (WEM) scenarios that only confirm existing policies, without increasing ambition. In other countries, such as Croatia, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovakia, PAMs lack detail and notably do not include a comprehensive assessment of their emission reductions. In other cases, such as Hungary, Italy and Lithuania, the ambition of PAMs needs substantial improvements in order to achieve the ESR targets. Slovenia has simply not presented any climate PAMs.

In the end, only four countries have developed plans that meet (Estonia, Lithuania) or surpass (Spain, Luxembourg) their ESR targets, and include credible emission reductions projections as well as PAMs that, while they could be improved, are sufficient and detailed enough to back them up. In all cases, however, they remain insufficient to be in line with a 1.5°C trajectory and in light of historical responsibilities. In addition, Estonia is not doing great, as it would still fail to meet its other 2030 EU binding requirement (the 2030 LULUCF target).

If too many countries underperform on their ESR targets, there will be scarcity of surplus emissions to be traded (as the ESR ‘flexibility’ would allow for a certain amount of emissions to be traded between EU countries). This scarcity paired with the higher demand would result in significantly higher prices for the emission allowances. This is important, because in this case countries with higher targets cannot economically rely on buying allowances to cover for their underperformance (as was the case for example in Germany for the 2013-2020 period). To prevent this scenario, all countries, even the ones with higher targets have to deliver domestic emission cuts according to their obligations – which would even be cheaper than having to deal with expensive traded allowances.

Besides the ESR targets, several Member States (seven of the 15 that submitted the draft updates) also have national binding economy-wide climate targets that should be integrated and reflected in their NECP updates.

Unfortunately, this is largely not the case in the available plans. The ambition levels in the draft NECP updates of Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands fail to achieve their respective national 2030 economy-wide targets; for Hungary, Portugal and Slovenia, existing and planned PAMs are insufficient to meet them. Several of them also have national long-term targets for climate neutrality, in some cases (Sweden) before 2050. The draft NECP updates largely fail to align with these long-term targets, for instance in Denmark, Luxembourg, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Sweden.

Besides submitted NECPs, preliminary drafts were available in Austria, Belgium, Czechia and Greece. Overall, they are also unfit to meet basic EU requirements. Austria would not meet its ESR target in the presented scenario with additional measures; Belgium would also not meet its ESR target, due to the lack of ambition of one of its regions (Flanders); Greece plans to surpass it, but has not presented any scenario with additional measures supporting its intentions; Czechia would surpass it in the scenario with additional measures, but it has not yet laid out any of the additional measures.

Increase the ambition on energy savings

The draft NECP updates show that the ambition level on energy savings is too low to reap the multiple benefits of energy savings for the people, the economy and for the climate. The newly revised 2023 Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) mandates that a minimum of 11.7% energy consumption reduction for 2030 needs to be reached. As a minimum, national energy efficiency contributions should at least add up to match this new EU energy efficiency target, while more is required for staying within 1.5°C of global warming. A reduction of energy consumption of at least 20% by 2030 is needed to stay in line with the Paris Agreement goals.

Overall, many countries fail to indicate a national contribution for energy efficiency. Among the countries that have submitted a draft to the European Commission, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands did not indicate a national contribution for both primary and final energy consumption for 2030. Additionally, Hungary, Slovakia and Luxembourg failed to indicate a national contribution for primary energy consumption, whereas Portugal did not indicate one for final energy consumption. Slovakia did not fully state a national contribution for final energy consumption, but indicates different levels of energy consumption.

Member States are not on track to achieve the EU 2030 energy efficiency target, taking into account that many Member States did not include yet a national contribution for energy efficiency and that many Member States did not yet submit their draft NECP update. We compared the national contributions for energy efficiency already submitted to the European Commission with the combined outcome of the benchmarks for national contributions as per the 2023 EED for these countries (methodology in Annex I of this report, where you also find a table with the benchmarks for national contributions). For primary energy, the contributions of 9 EU Member States alone that have already submitted their contributions, fall short by around 30.1 Mtoe to the agreed EU target. This constitutes an ambition gap of around 11%. In terms of final energy, the distance to the EU binding energy efficiency target is around 14.8 Mtoe, which constitutes an ambition gap of around 76.5% for final energy consumption compared to what 101 Member States combined should have planned.

Considering that this ambition gap exists already for the small group of Member States that have submitted their national contributions, Member States with many large energy consumers like Germany and France not even taken into account, this does not bode very well for the achievement of the EU’s 2030 energy efficiency target. National contributions combined only reach around 30% of the EU energy efficiency target, taking into account only national contributions that were submitted to the European Commission

Only Lithuania submitted a national contribution in line with the EU 2030 energy efficiency target in both primary and final energy terms, meaning that it complies with the formula of the 2023 EED. Estonia and Italy on the other hand indicate national contributions for final energy consumption that use the legal option of a 2.5% deviation from the formula. This is still compliant with the 2023 EED, but not enough to be fully in line with the EU energy efficiency target for final energy consumption. Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden indicate a national contribution for 2030 that is not ambitious enough for the reduction of energy consumption needed to align with the 2030 EU energy efficiency target. It can be noted that Czechia’s not yet submitted draft NECP’s national contribution seems to be formally in line with the 2030 EU energy efficiency target. However, all countries need to step up efforts to go beyond minimum requirements and get on the right track to surpass these and align with 1.5°C trajectories.

From the submitted draft NECP updates, there are two countries that unfortunately indicate a higher energy consumption in 2030 compared to today (based on the latest 2021 Eurostat data). Cyprus indicates an increased energy consumption in 2030 compared to 2021 for final energy consumption and Portugal indicates a higher primary energy consumption compared to 2021.

Energy efficiency measures are often missing and too vague. Whereas Slovenia does not specify any energy efficiency measures, Denmark, Estonia, Finland and the Netherlands only mention existing measures or as per 2019 NECP. The majority of countries which submitted their draft NECP update to the Commission, such as Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Sweden, list many measures without the necessary level of detail, including without a quantification in terms of energy savings per measure. From the preliminary drafts, Austria and Greece lack details and Czechia still refers mostly to measures already present in the 2019 NECP.

Increase the ambition of renewables

The RED revision increased the EU 2030 renewable energy target. The binding target was increased from 32% to 42.5%. Additionally, the RED revision also included an additional 2.5% indicative top up that would allow the EU to reach 45%. However, a renewable energy target of at least 50% by 2030 would be needed to put the EU on track with a 1.5°C trajectory. When Member States had to submit their draft NECP updates by June 2023, they needed to include a national renewable energy contribution that should contribute to the EU 2030 renewable energy target. It is however still unclear what measures will be taken in case the Member States contributions are not enough to reach the indicative 45% EU renewable energy target.

In its recommendations, the European Commission will assess the national renewable contributions, based on the formula set out in Annex II of the Governance Regulation (referred to as the Governance Regulation formula benchmark). As the European Commission has chosen not to publicly disclose these benchmarks which correspond to the EU 2030 renewable energy target of 42.5% and 45%, a comprehensive assessment of the national renewable energy contributions is currently not possible. As only benchmarks in line with a 40% EU renewable energy target are publicly available, we used these data to make careful assessments of the available national renewable energy contributions.

The current draft NECP updates only give a partial overview of the national renewable energy contributions. Some countries, such as the Netherlands and Sweden indicated they would include updated national renewable energy contributions in their final updated NECPs (when the RED revision process will have come to an end).

As not all Member States submitted their draft NECP updates or as some submitted draft NECP updates did not include national renewable energy contributions, we cannot assess if an EU renewable energy target of 42.5% or 45% is within reach. But even without the publication of the Governance Regulation Formula benchmarks, we noticed there are several Member States that have put forward national renewable energy contributions which will not be enough to be in line with the EU 2030 renewable energy target of 42.5% let alone 45%. Examples are Cyprus, Slovenia and Slovakia.

When looking at the national renewable energy contributions included in the NECPs, it is also important to look at the history and what happened in the past few years. France did not reach its national legally binding renewable energy target in 2020. In 2021, four Member States (France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Romania) went below their baseline share (equal to its binding national renewable energy target in 2020). Member States will have to take additional measures to ensure they are on a trajectory in line with the Paris Agreement goals.

Some NECP updates fall short in terms of policies and measures (PAMs) supporting the updated national renewable energy contribution. Key issues include inadequate projections with additional measures not aligning with national renewable energy contribution (Cyprus, Slovakia), and in some cases lack of clear timeframes or binding nature of measures (Luxemburg, Portugal).

There are positive developments in solar energy, in particular related to the enhancement of measures for small scale rooftop solar PV. In Cyprus, for example, financial support is foreseen for vulnerable consumers to install solar PV, though details are missing. However, areas of concern remain. Italy underestimates the capacity for installation of renewables, despite studies indicating a much higher potential than in the NECP update. Portugal could be more ambitious with regards to decentralised solar. Slovenia needs to step ahead and significantly increase its current renewables ambition, after being at the tail end of EU Member States in terms of newly installed solar and wind capacity in past years. The plan from Luxembourg only includes two solar PAMs, with a narrow scope: one only focuses on new buildings, excluding existing ones; the other, for industrial and agricultural buildings, only focuses on “PV-ready” buildings instead of introducing an overall installation obligation.

There is room for improvement with regards to wind. The current uncertain framework for renewables hinders investment confidence. Particularly in Hungary, there is an urgent need to lift legal restrictions on wind energy. In Czechia, new wind power installations are hampered by long and complicated administrative procedures and lack of political support.

PAMs related to bioenergy also raise concerns. Denmark’s plan relies heavily on unsustainable volumes of imported wood biomass. Portugal promotes better use of biomass for energy purposes, but without including an assessment of the potential of residual biomass, nor mentioning the cascading principle in its use. The plan of Spain is missing information on the origin, type and quantities of forest and agricultural biomass that corresponds to the 2030 renewables target. Other countries, such as Lithuania and Slovenia, include PAMs that favour bio-energy without ensuring they do not hamper biodiversity and carbon sinks, and at the expense of other renewable sources such as wind and solar.

Streamlining permitting remains a persistent challenge. As part of the REPowerEU RED revision, there has been a lot of discussion about streamlined permitting. In the EC’s guidance for the Member States on the update of the NECPs (December 2022), it was highlighted that a particular challenge that needs to be addressed by the NECP updates concerns permitting. Yet, it’s concerning to see the limited focus on this in several draft NECP updates. Italy’s plan does not sufficiently address the major hurdle in the development of RES facilities, primarily associated with the challenge of concluding authorization processes within definite and sustainable timeframes. Slovakia’s plan lacks measures on acceleration of renewables and to overcome identified barriers. In Czechia, the preliminary draft introduces measures to simplify administrative procedures for renewables and for acceleration zones but lacks details, including on their expected impact. It would be crucial for Slovenia to include measures tackling issues of lack of staff capacity for deployment of renewables.

While the draft NECP updates also offered the opportunity to strengthen PAMs with regards to energy communities, varied approaches among Member States reveal both progress and missed opportunities, with some plans introducing promising measures and others lagging in concrete implementation. Croatia added a new measure to encourage energy sharing and establishment of energy communities. Lithuania incorporated financial support for energy poverty reduction to municipality-led renewable energy communities. In Cyprus, the regulatory framework is set to be completed by 2024. On the other hand in Spain, despite the latest advances in regulation for renewables self-consumption, local energy communities are still waiting for their legal framework. The plans of Estonia and Slovenia are missing measures promoting energy communities. Italy added strategies and actions also supporting self-consumption and the fostering of renewable energy communities, but these often seem more like broad intentions without a detailed, time-bound implementation plan. Portugal still undervalues the potential of decentralised energy production and energy communities in their plan. And even though Czechia mentioned support of energy communities and energy sharing in the draft plan (not submitted yet), it is noticeable that it still did not fully transpose RED II.

Develop more robust policies and measures

The NECPs need to include strong policies and measures (PAMs) that will substantiate the delivery of the 2030 climate and energy targets. This means that PAMs should be described clearly and in detail, and they should be comprehensive, credible, quantified and based on up-to-date information. Most Member States still have much work to do to ensure that the existing and additional PAMs described in the plan are up to the task, before the final plans are submitted in June 2024. In the current draft NECP updates, PAMs still have large margins of improvement.

Some countries, such as Denmark, Estonia and Finland, have not presented any additional PAMs, while Slovenia did not present any PAMs at all. It goes without saying that this must be addressed as a priority in the final NECPs update or in a revised draft plan. Other countries (Cyprus and, among those that have not submitted a draft, Belgium) would likely require more measures to achieve the targets set in the plans, or could achieve them more easily by taking into account other dimensions (for instance, Lithuania and Luxembourg are weak on regulatory and behavioural measures respectively).

In most countries, however, PAMs simply do not have the level of detail that is required to assess whether or not they support the targets set in the plans. For countries such as Czechia, Greece, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovakia and, to some extent, Croatia and Spain, measures require more details on timeframes, planned actions and prioritisation among measures. In several cases, the assessment of their impacts is either absent or not detailed enough. The impact of PAMs on emission reductions is not adequately addressed in countries such as Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, the Netherlands, Portugal and Slovakia. Several plans are also lacking an analysis of PAMs impact on the environment (Austria, Croatia, Spain), the social dimension (Slovakia) or both (Belgium, Czechia, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden).

Last but not least, countries are also supposed to look into how much funding they need to implement each PAM, and which sources will be used to get it. This aspect should also be drastically improved in the final NECP updates, compared to the current ones. On investment needs, several plans either include incomplete explanations (Czechia, Sweden) or completely lack them (Austria, Greece, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia). In some cases, investment needs are provided but lack methodology (Croatia) or are not credible (Cyprus). Explanations on funding sources are incomplete or missing for Austria, Finland, Greece, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Sweden. In Lithuania, PAMs are financed without duly taking the polluter pays principle into account. Finally, the integration and use of EU funds in the plans could be improved in several plans, including those of Cyprus, Czechia, Hungary Slovenia or Denmark, where EU funds are used to fund measures previously funded by the state.

Phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible

- Phase out coal as soon as possible

To be in line with a 1.5°C pathway, the EU must phase out coal by 2030. This implies that coal phase-out plans should already be well underway across the EU, and clearly reflected in the draft NECP updates. This should be facilitated by the fact that planning for coal regions was already addressed in the Territorial Just Transition Plans (TJTPs).

Unfortunately, some concerning elements emerge from the draft plans. In Croatia, Slovenia and Czechia, coal will continue to play an important role in the energy mix beyond 2030, with possibilities for earlier exit dates not sufficiently considered. In Croatia, coal would be fully phased out only as late as 2040, leaving existing coal plants untouched before 2030. In Czechia, lignite mining risks being prolonged until 2035 despite the government’s commitment to phase out coal usage by 2033. Worryingly, both Hungary and Italy have delayed their coal phase-out plans compared to the 2019 NECPs. Hungary has delayed the phase-out of the Matra power plant, in contradiction with its TJTP; while in Italy, coal power plants in Sardinia will only be phased out as late as 2028 (and not in 2025 as formerly planned). Some countries, such as Hungary, Italy and Slovakia, plan to transition from coal to fossil gas power generation, which is doubtfully in line with decarbonizing the energy mix. All these choices move away from the Paris agreement objectives and are costly for European citizens.

Estonia, where oil shale is the main fossil fuel, is a case on its own. Unfortunately, the Estonian draft NECP update projects oil shale production to remain unchanged until 2030, and does not project any deadline for its phase-out, despite it being present in the TJTP.

- Halt fossil gas expansion and plan its phase-out

To be in line with a 1.5°C pathway, the EU must phase out fossil gas by 2035. In their NECP updates, Member States should therefore include plans for its progressive phase-out, and prioritise investments in clean energy solutions that will truly speed up the transition.

The draft NECP updates submitted so far tell a different story. In the vast majority of countries, there are no plans for fossil gas infrastructure decommissioning, nor clear exit dates. Only Portugal plans to phase out fossil gas by 2040 (which remains too late), while Luxembourg and Austria have phase-out dates only for some sectors. However, in all cases decommissioning timelines and strategies remain too vague, and Portugal directly contradicts its target with some planned measures to expand LNG infrastructure. Maintaining fossil gas infrastructure bars the way to a system-switch towards energy savings and renewables.

Significant expansion of fossil gas infrastructure is actually envisaged in several plans, in countries such as Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia and Slovenia. Italy has set plans to double the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline pipeline and to finalise the Melita pipeline, which connects it with Malta. In Cyprus, fossil gas is seen as the cornerstone of the energy transition and as a fundamental decarbonisation tool. Currently absent from the energy mix, fossil gas is projected to represent the main source of electricity generation in Cyprus already in the coming years. Investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure risks creating lock-in effects and stranded infrastructure assets; the EU already has substantial fossil gas overcapacity and does not need more.

Stay away from false solutions

In some cases, Member States fail to prioritise investments in bulletproof climate or energy solutions, and instead prefer to bet too much on solutions that will not deliver the transition to a 100% renewables-based energy system that the EU truly needs.

In several of the plans – including Cyprus, Denmark, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain and, based on preliminary drafts, also Austria and Czechia – there is an over-reliance on CCS and CCU technologies in reducing emissions. This is despite the fact that such technologies have so far consistently proven unreliable, as well as energy-intensive, economically inefficient and play a role in prolonging fossil fuels use.

In some plans, nuclear power also plays an important role. Notably, both Czechia and Slovakia plan to substantially increase its expansion. Czechia plans the construction of at least 3 conventional reactors and at least one SMR, while Slovakia sees it as key for its energy security and decarbonisation. This reliance on nuclear expansion to meet energy targets, coming at the expense of renewables, is misplaced – especially given nuclear’s costs and long (often unrealistic) construction timelines.

Hydrogen is not a false solution in itself, provided that it is exclusively based on renewables and, being a limited source, that its use remains limited where most needed, notably in hard-to-abate industrial sectors. However, some countries such as Hungary, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, but also Belgium, are planning a significant expansion of hydrogen capacity, however it’s not always clear how it will be generated and used. The unregulated expansion in hydrogen use risks to give the fossil gas industry the perfect excuse for continued fossil gas investments and to generate lock-in effects.

Plan to phase out fossil fuel subsidies

In their NECPs, Member states are required to report all their energy subsidies, including fossil fuels subsidies and, if they exist, report policies and plans to phase them out. They are also expected to monitor progress in the National Energy and Climate Progress Reports (NECPRs). The NECPs planning and monitoring process should therefore be an opportunity for transparency and for planning towards a socially just transition, as fossil fuel subsidies disproportionately benefit the middle and upper classes.

Unfortunately, as it happened for the 2019 NECPs, the available draft NECP updates show significant gaps on subsidies reporting and phase-out plans. 6 out of the 15 countries that have submitted a draft did not make any list of fossil fuel subsidies available (Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia) and such list does not appear also in the preliminary drafts of Austria and Greece. Other countries have provided a list, which however is either incomplete (Cyprus, Estonia, Slovenia) or fails to recognize indirect and implicit fossil fuel subsidies (Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Portugal). Also, none of the drafts analysed (including preliminary ones) include a comprehensive and detailed plan for their phase-out. Portugal and Belgium intend to phase them out by 2030, but they all lack detailed plans, with clear timelines and concrete targets. Lithuania’s phase-out plan, instead, is only valid for some subsidies.

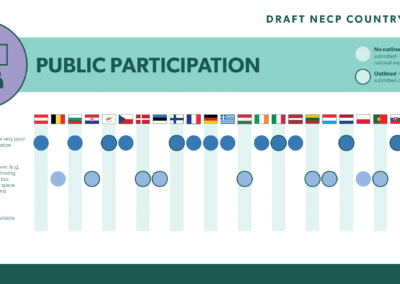

Significantly improve public participation

According to the Governance regulation and the Aarhus Convention, Member States must organise early and effective public consultations when all options are still open, prior to the submission of draft and final NECPs. They must also establish a Multilevel Climate and Energy Dialogue to discuss energy and climate policies, including NECPs. During this round of revision, compliance to such requirements ranged from poor to non-existent. Member States should significantly improve public participation processes before the submission of their final NECP updates.

- Public consultations

In the vast majority of EU Member States, some form of public consultation took place – but most often, several minimum legal requirements either of EU law or the Aarhus Convention were missing. Only in Lithuania and Belgium (with the exception of the Flanders) CSOs found public consultations satisfactory.

Member States must also ensure that the public is given early opportunities to participate in the preparation of the draft NECP update. Despite this legal requirement, some consultations were organised late, and some even after the 30 June deadline for submission of the draft NECP update to the European Commission (Austria, Cyprus). Public consultations must take place when all options are still available, which was clearly not the case in several countries where everything was already decided when the consultation took place (Denmark, Estonia, Hungary).

Sufficient information must be provided as part of the public consultation process, including and most importantly the draft NECP. However, in several countries, the draft NECP was not shared during the consultation (Cyprus, Portugal, Czechia and France) or was shared, but too late to provide meaningful input (Cyprus, Slovakia, Spain) or incompletely (for instance in Hungary). In many cases, scenarios with additional policies were not presented (including in Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia and Spain). Effective public consultations were hampered by the short timeframe to provide comments (Czechia, Slovakia, Croatia, Luxembourg) or the limited space to provide feedback (Czechia, Poland, Portugal).

Several countries did not organise any form of public consultation specifically around the NECP update. This includes most of the 12 Member States that did not submit their draft NECP updates, such as Bulgaria, Ireland, Germany or Poland.

- Multilevel Climate and Energy Dialogues (MCED)

According to Article 11 of the Governance Regulation, NECPs should be discussed in the framework of Multilevel Climate and Energy Dialogues (MCED). Some countries simply did not set up a MCED, for instance Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Ireland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

In several countries, an MCED exists in some form (for instance in Croatia, Portugal, Lithuania or France) but recommendations were only considered in a small amount by the government (Luxembourg), the MCED was not well-known (Cyprus), its expected impact on the draft was very unclear (Austria), or the MCED is not a permanent structure and consists of ad-hoc meetings (Hungary). In several countries, an MCED has been put in place but with one or several key actors missing: the general public (Estonia), local authorities (Hungary) or the private sector (Portugal).

In the vast majority of Member States that have not submitted their draft NECP update, MCEDs were not used as a platform to discuss these plans.

DOWNLOAD FULL NECP ASSESSMENT REPORT

PREVIOUS

NEXT